Classifying Columns: Set-valued features and Hierarchical Priors

Gain intuition on hierarchical priors by building a Naive Bayes classifier for table columns

Many real-life problems co ntain features that do not fit into a feature vector - even in simple settings. Here is one example: Our observed data consists of columns (from a table). Each column has a header and the body containing its values. We consider rows to be unordered, so that the body is a (multi-)set-valued feature. The number of rows can differ from observation to observation.

The exchangeability and varying number of rows can be easily accomodated in a Naive Bayes-style classifier. We denote the class label by \(c\), the header by \(h\), and the body by \(B\). Conditionally independent features translate into the probability

\[\log p(h, B \mid c) = \log p(h \mid c) + \sum_{x \in B} p(x \mid c)\]There is a problem with this approach: The log-probabilities for the body scale linearly with the number of rows, so that the information in the header is completely ignored if there are sufficiently many rows - the same holds for the class distribution \(p(c)\). Similarly, we can expect classifications to be too confident in this case because even miniscule differences between classes are magnified.

The problem is the linear scaling, which in turn is due to the underlying independence assumption. To resolve this, the rows need to be dependent. Since they are unordered, their distribution should still be exchangeable.

All of this is achieved by injecting a latent variable between the class label and the observations,

\[p(B \mid c) = \int \left[\prod_{x \in B} p(x \mid \theta)\right] \, p(\theta \mid c)\, d\theta\]All exchangeable distributions can be represented like this (that’s de Finetti’s theorem), but in practice an exponential family for \(p(x \mid \theta)\) and a conjugate prior for \(p(\theta \mid c)\) can be reasonable choices, since then the integral can be evaulated in closed form.

Let’s focus on Bernoulli observations and a Beta prior since this is easy to understand. The rows can be summarized by the sufficient statistics \(k\) (number of ones) and \(n\) (number of rows):

\[\prod_{x \in B} p(x \mid \theta) = \theta^k (1 - \theta)^{n - k}\]which has the same functional form as the Beta-prior

\[p(\theta \mid c) = \frac{1}{Z(\alpha_c, \beta_c)} \, \theta^{\alpha_c} (1 - \theta)^{\beta_c}\]so that the integral evaluates to

\[p(B \mid c) = \frac{Z(\alpha_c + k, \beta_c + n - k)}{Z(\alpha_c, \beta_c)}\]This is all basic mechanics of exponential families, now how can we understand the behavior? First we reparametrize the sufficient statistics using counts \(n\) and mean \(p = k\,/\,n\). Similarly, for the prior set

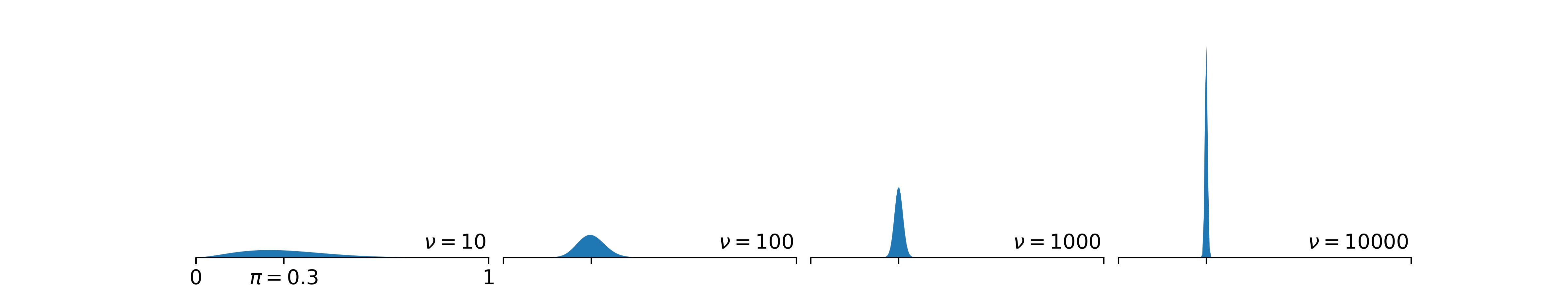

\[\begin{align} \alpha &= \pi \nu \\ \beta &= (1 - \pi) \nu \end{align}\]Here is the pdf of the Beta distribution for fixed \(\pi\) for various \(\nu\):

In particular, for \(\nu \rightarrow \infty\), it approaches a delta function, so that e.g.

\[\lim_{n \rightarrow\infty} \int_0^1 d\theta\, \theta^{p n} (1 - \theta)^{(1 - p) n} \, \text{Beta}(x \mid \alpha, \beta) = \text{Beta}(p \mid \alpha, \beta) \, \int_0^1 d\theta\, \theta^{p n} (1 - \theta)^{(1 - p) n}\]- If \(\nu\rightarrow\infty\), \(p(B \mid c) \propto \pi_c^k (1 - \pi_c)^{n - k}\), which is just the same as for conditionally independent variables.

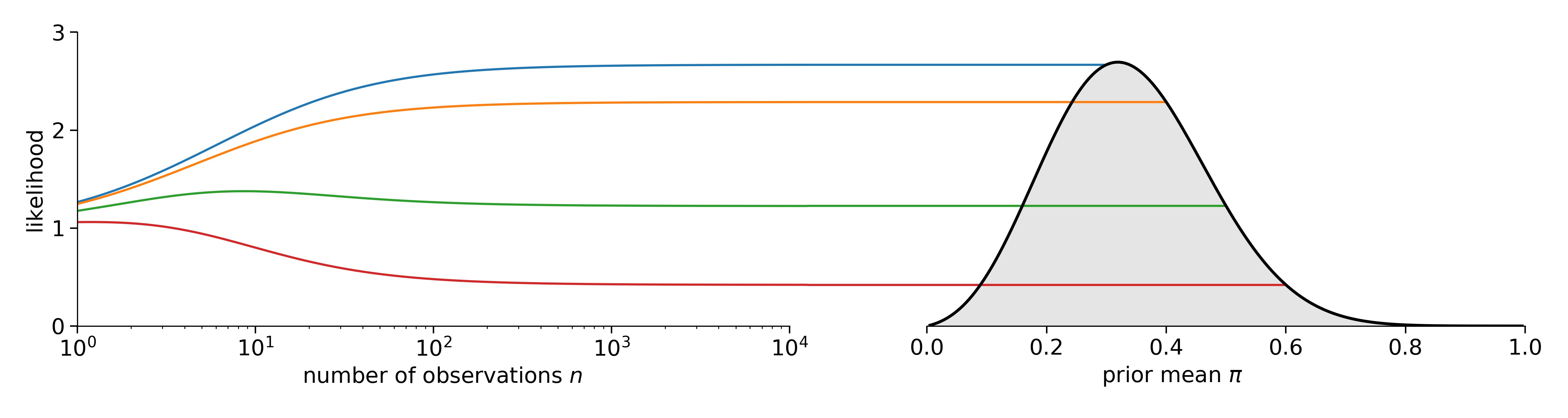

- If \(n\rightarrow\infty\), we get \(p(B \mid c) \propto \text{Beta}(p \mid \alpha_c, \beta_c)\), which only depends on the mean value \(p\), while the part that scales with \(n\) is independent of the prior parameters.

The latter happens because in this limit, \(\theta = p\) regardless of the value of \(\pi\), i.e. the latent variable adjusts to the data perfectly regardless of the prior.

Below is the likelihood divided by the limiting constant \(\int_0^1 d\theta \, \theta^n (1 - \theta)^{n - k} = Z(k + 1, n - k + 1)\), with the corresponding points of the Beta-likelihood indicated to the right:

Intuitively, once the number of rows is much larger than the prior pseudo-counts, the mean is used for classification. If there are very few rows, the sum is used which incorporates the uncertainty of the observed mean.